Rigger Meaning: Everything You Need to Know About This Essential Trade

Ever watched a massive crane lift a multi-ton steel beam hundreds of feet into the air and wondered, “Who’s making sure that thing doesn’t come crashing down?” Or seen behind-the-scenes footage of a concert where enormous light rigs hang above thousands of fans and thought, “Someone’s responsible for all that staying up there, right?”

That someone is a rigger. And while it might not be the most glamorous job title out there, it’s absolutely one of the most critical. When riggers do their job right, everything runs smoothly. When they don’t? Well, let’s just say the consequences can be catastrophic.

If you’ve been curious about what riggers actually do, or you’re considering a career in rigging, you’re in the right place. Let’s break down everything you need to know about this essential trade.

What Is a Rigger? The Definition Explained

Here’s the straightforward answer: A rigger is a skilled tradesperson who specializes in lifting, moving, and positioning heavy equipment or materials using specialized rigging gear like ropes, cables, chains, pulleys, and hoists.

But that definition, while accurate, doesn’t really capture the full picture. Let me paint it better for you.

Imagine you’re building a 50-story skyscraper. You need to get tons of steel, concrete panels, HVAC systems, and construction equipment to various floors. Or picture yourself setting up a major music festival where massive speaker arrays and lighting rigs need to hang safely above the stage. Maybe you’re working on an oil rig in the middle of the ocean, moving critical machinery in harsh conditions.

In all these scenarios, you can’t just tie a rope around something heavy and hope for the best. You need someone who understands:

- Weight distribution and load calculations

- The strength and limitations of different rigging equipment

- Physics principles like center of gravity and mechanical advantage

- Safety protocols that prevent accidents and deaths

- How to communicate effectively with crane operators and crew members

That’s a rigger. They’re the problem-solvers who figure out how to safely move things that weigh more than most people will ever encounter in their lifetime.

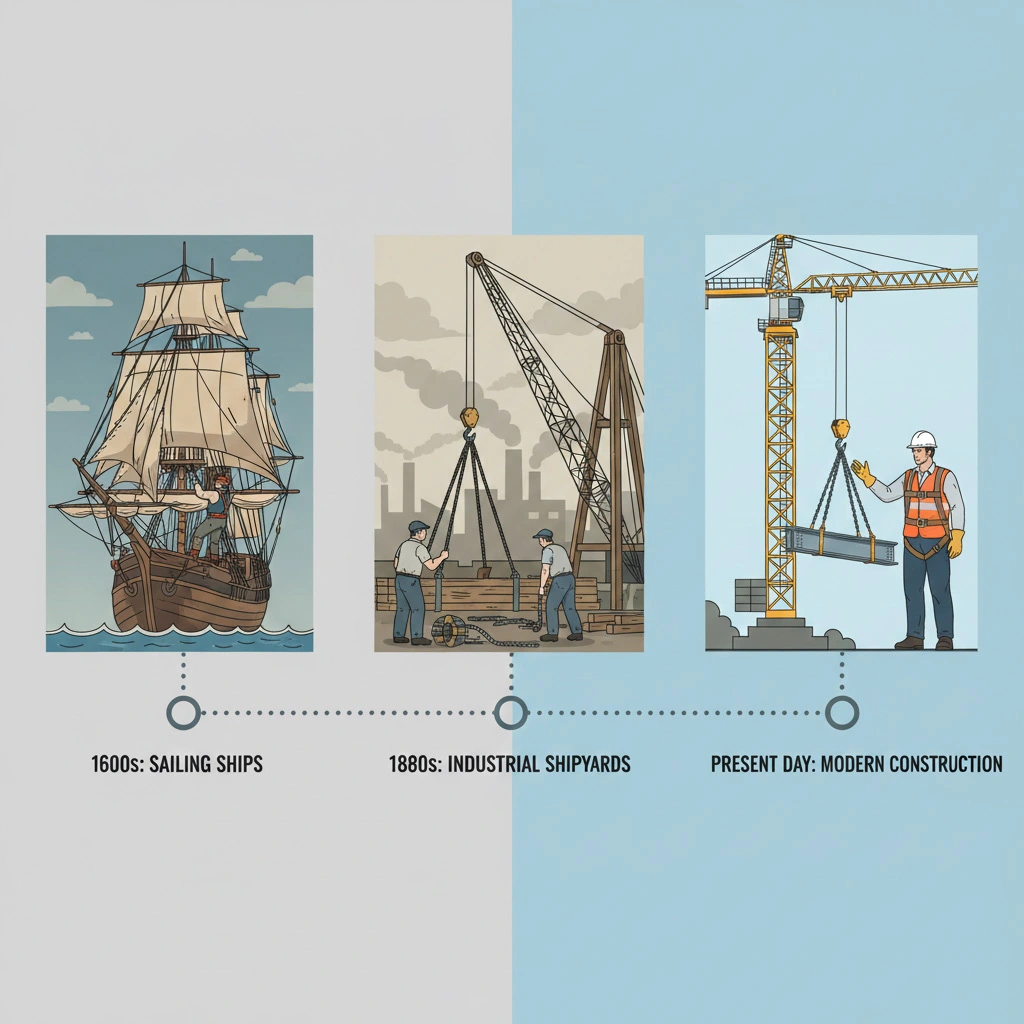

The Origins: Where Does the Word “Rigger” Come From?

The term “rigger” has nautical roots that date back to the early 1600s. Originally, riggers were the sailors who worked with the rigging on ships—the complex network of ropes, chains, and tackle used to support the masts and control the sails.

These maritime riggers were masters of rope work. They knew dozens of knots, understood how to create mechanical advantage using pulleys and blocks, and could calculate loads and forces before any modern engineering existed. Their expertise with ropes and lifting became invaluable not just at sea, but on land too.

When the Industrial Revolution kicked into gear and heavy machinery became commonplace, there was a need for people who could move this equipment safely. Who better than riggers who already understood the principles of lifting and load management? The profession evolved from ships to shipyards, then to construction sites, manufacturing plants, and eventually every industry that deals with heavy equipment.

Today’s riggers still use many of the same fundamental techniques their seafaring predecessors developed centuries ago. The equipment’s gotten more sophisticated—we’ve added steel cables, synthetic slings, and hydraulic systems—but the core principles remain remarkably similar.

What Does a Rigger Actually Do? Day-to-Day Responsibilities

Let’s get into the nitty-gritty of what riggers do on a typical workday. Spoiler alert: it’s way more complex than “attach stuff to cranes.”

1. Load Assessment and Planning

Before anything gets lifted, riggers need to assess what they’re dealing with. This means:

Calculating Weight: You can’t just eyeball a massive steel beam and guess. Riggers need to know exact weights, which might involve reading blueprints, checking manufacturer specifications, or using load cells.

Determining the Center of Gravity: A load that’s unevenly weighted will swing, shift, or flip during a lift. Riggers identify the center of gravity and plan attachment points accordingly. Get this wrong, and you’ve got a multi-ton pendulum swinging wildly through the air.

Creating a Rigging Plan: For complex lifts, riggers develop detailed plans that outline every step—what equipment to use, where to attach it, the lifting sequence, potential hazards, and emergency procedures. Nothing happens by chance.

2. Equipment Inspection and Selection

Rigging equipment takes a beating. Cables fray, chains develop cracks, and shackles can become deformed under extreme loads. Part of a rigger’s job is being obsessively vigilant about equipment condition.

Daily Inspections: Before each shift, riggers inspect every piece of equipment they’ll use—looking for wear, damage, corrosion, or anything that might indicate weakness. A damaged sling that looks “probably fine” can snap under load, with deadly consequences.

Selecting the Right Gear: Different situations require different equipment. Riggers choose appropriate:

- Slings (wire rope, synthetic, chain) based on load type and environment

- Shackles and hooks rated for the expected forces

- Pulleys and blocks that can handle the weight and provide needed mechanical advantage

- Hoists and winches suitable for the lift

Using equipment beyond its rated capacity isn’t just dangerous—it’s often illegal and can result in criminal charges if something goes wrong.

3. Setting Up the Rigging

This is where theory meets practice. Riggers physically set up the equipment that will lift and move loads.

Attaching Rigging to the Load: Using techniques like basket hitches, choker hitches, or bridle hitches, riggers secure slings around the load. The attachment method affects the load capacity—use the wrong hitch, and your sling might only be rated for half its normal capacity.

Connecting to Lifting Equipment: Whether it’s a crane hook, a chain hoist, or a come-along, riggers make secure connections using properly rated hardware. They double-check that everything’s locked, latched, and properly aligned.

Applying Taglines: These are ropes attached to the load that workers on the ground can use to control rotation and prevent swinging. On windy days or in tight spaces, taglines are essential for maintaining control.

4. Communication and Signalling

Construction sites and industrial facilities are loud. Really loud. Riggers can’t just shout instructions to crane operators who might be hundreds of feet away.

Standard Hand Signals: The industry uses standardised hand signals for communicating with crane operators. A rigger might signal “hoist,” “lower,” “swing left,” “stop,” or “emergency stop” through specific gestures that are instantly recognisable.

Radio Communication: For complex operations or when visual contact isn’t possible, riggers use two-way radios to coordinate with crane operators and other team members.

Team Coordination: Large lifts often involve multiple riggers, crane operators, spotters, and other personnel. The lead rigger coordinates all these moving parts, ensuring everyone knows their role and the operation proceeds safely.

5. Monitoring the Lift

Once the load’s in the air, the rigger’s job is far from over. They actively monitor the entire operation.

Watching for Problems: Is the load swinging more than expected? Are any components showing signs of stress? Is anyone in the danger zone? Riggers maintain constant vigilance.

Making Adjustments: Sometimes mid-lift corrections are necessary. A rigger might signal the crane operator to pause while they reposition taglines or clear an unexpected obstacle.

Ensuring Safe Placement: When the load reaches its destination, riggers guide it into position and ensure it’s set down safely before releasing the rigging.

6. Post-Lift Procedures

After the load’s successfully moved, there’s still work to do.

Disconnecting Rigging: Riggers carefully remove all equipment from the load, ensuring nothing remains attached that could create a hazard.

Inspecting Equipment Again: After use, the equipment gets another inspection to check for any damage that occurred during the lift.

Storing Equipment Properly: Rigging gear needs to be stored correctly—coiled ropes, organised chains, protected from the elements—to maintain its condition and make it easy to inspect next time.

Documenting the Operation: For major lifts, riggers often complete paperwork documenting what equipment was used, any issues encountered, and confirming the operation was completed safely.

Different Types of Riggers: Specialised Roles

Not all riggers do the same work. The profession has specialised into several distinct types based on industry and specific skills.

Construction Riggers

These are probably the riggers you’ve seen if you’ve ever walked past a building site. Construction riggers work on:

High-Rise Buildings: Moving steel beams, concrete panels, HVAC units, and construction equipment to various floors. They often work at significant heights and deal with changing conditions as buildings rise.

Bridge Construction: Handling massive structural components, often working over water or highways where a dropped load could be catastrophic.

Infrastructure Projects: Moving heavy machinery, precast concrete sections, and materials for roads, tunnels, and public works.

Construction riggers need to be incredibly versatile because every project presents new challenges and no two lifts are exactly alike.

Entertainment Riggers

If you’ve ever been to a concert, theater production, or major event, entertainment riggers made sure the equipment over your head stayed there.

Concert Rigging: Hanging massive speaker arrays (some weighing several tons), lighting trusses, LED screens, and pyrotechnic rigs in venues from small clubs to massive arenas.

Theater Productions: Installing flying systems that lift actors, managing complex curtain rigging, and creating elaborate scenic elements that move during performances.

Film and TV Production: Setting up lighting rigs, green screens, camera platforms, and special effects equipment on sets.

Entertainment riggers often work to extremely tight deadlines—a concert might go up in hours, perform, then come down overnight before moving to the next city.

Maritime and Offshore Riggers

These riggers work in some of the most challenging environments imaginable.

Port Operations: Loading and unloading cargo ships, handling containers, securing goods for transport across oceans.

Offshore Oil and Gas Platforms: Moving drilling equipment, pipe sections, and machinery on platforms in the middle of the ocean, often in harsh weather conditions.

Ship Building and Repair: Working in shipyards to construct new vessels or refit existing ones, handling everything from hull sections to engine components.

Maritime riggers must be comfortable working in wet, salty environments that are hard on equipment, and they need additional skills like understanding maritime regulations and tidal effects.

Industrial Manufacturing Riggers

In factories and manufacturing plants, riggers handle equipment installation and maintenance.

Machine Installation: When new production equipment arrives—massive presses, injection molding machines, industrial robots—riggers move them into position.

Plant Maintenance: During shutdowns, riggers help remove and reinstall equipment for overhaul or replacement.

Assembly Line Management: Moving components along production lines, adjusting equipment positions, and reconfiguring layouts.

Manufacturing riggers often work in confined spaces and need to minimize downtime—every hour production is stopped costs money.

Specialized Riggers

Some riggers develop expertise in highly specific niches:

Aircraft Riggers: Work on helicopters and planes, handling control surfaces, flight controls, and delicate aircraft components.

Parachute Riggers: Specialize in packing, maintaining, and inspecting parachutes—precision work where mistakes can be fatal.

Telecommunications Riggers: Climb towers to install antennas, cables, and communications equipment, often at extreme heights.

Rescue Riggers: Trained in high-angle rescue, confined space rescue, and other emergency situations requiring rigging expertise.

Essential Skills Every Rigger Needs

So what does it take to be a successful rigger? It’s not just about being strong (though that helps). Here are the critical skills:

Physical Capabilities

Strength and Endurance: Rigging is physically demanding. You’re handling heavy equipment, working in uncomfortable positions, and staying on your feet for long shifts.

Comfort with Heights: Many rigging jobs involve working on scaffolding, aerial lifts, or building structures. If you’re afraid of heights, this isn’t the career for you.

Manual Dexterity: Tying specialized knots, connecting hardware, and manipulating equipment requires good hand-eye coordination and fine motor skills.

Physical Fitness: The work can be grueling, especially in extreme weather. You need stamina to maintain focus and performance throughout long days.

Technical Knowledge

Mathematics: Load calculations, angle computations, capacity ratings—riggers use math constantly. You need to understand basic geometry, trigonometry, and be comfortable with fractions and decimals.

Physics Understanding: Concepts like center of gravity, mechanical advantage, force vectors, and load dynamics aren’t just academic—they’re practical tools riggers use daily.

Equipment Expertise: Knowing the strengths, limitations, and proper use of dozens of different tools and pieces of equipment. This knowledge comes from training and experience.

Blueprint Reading: Riggers often work from construction drawings, load charts, and engineering diagrams. Being able to read and interpret these documents is essential.

Safety Consciousness

Hazard Recognition: The ability to spot potential dangers before they become actual problems. Experienced riggers develop an almost sixth sense for what could go wrong.

Attention to Detail: Missing a frayed cable, forgetting to lock a shackle, or miscalculating by a few degrees can have catastrophic consequences. Riggers need to be meticulously careful.

Following Procedures: OSHA regulations, manufacturer specifications, company protocols—there are rules for good reasons, and riggers need to follow them consistently.

Risk Assessment: Every lift involves some risk. Good riggers assess those risks, implement appropriate controls, and know when to stop an operation that’s too dangerous.

Communication Skills

Clear Verbal Communication: Whether it’s coordinating with team members, talking to supervisors, or explaining safety concerns, riggers need to communicate effectively.

Teamwork: Rigging is almost never a solo activity. Success depends on everyone working together, understanding their roles, and trusting each other.

Problem-Solving: When things don’t go as planned (and they often don’t), riggers need to think on their feet and develop safe solutions quickly.

How to Become a Rigger: Education and Training

Interested in pursuing rigging as a career? Here’s what the path typically looks like.

Educational Background

High School Diploma or Equivalent: This is the baseline. Strong performance in math, physics, and technical courses will serve you well.

Vocational/Technical Training: Many community colleges and technical schools offer programs in rigging, construction technology, or industrial maintenance that include rigging components.

Apprenticeships: This is arguably the best path. Apprenticeship programs combine classroom instruction with paid on-the-job training under experienced riggers. You’re earning while you’re learning.

Certifications and Qualifications

NCCCO Certification: The National Commission for the Certification of Crane Operators offers rigger certifications (Rigger Level I and Level II) that are widely recognized across industries.

OSHA Training: Completing OSHA 10-hour or 30-hour construction safety courses provides foundation knowledge in workplace safety.

Specialized Certifications: Depending on your intended specialty, you might pursue additional certifications like:

- Entertainment rigging certifications (ETCP)

- Offshore rigging qualifications (OPITO)

- Scaffold user/builder certifications

- Confined space entry certifications

- Fall protection training

First Aid/CPR: Many employers require or prefer riggers to have current first aid and CPR certifications.

Experience Requirements

Entry-Level Positions: You might start as a rigger helper or apprentice, learning the basics while assisting experienced riggers.

Progressive Responsibility: As you gain experience, you’ll take on more complex lifts and eventually lead rigging operations.

Continuing Education: The best riggers never stop learning. New equipment, changing regulations, and evolving techniques mean ongoing training is important.

Safety in Rigging: Why It’s Absolutely Critical

Let’s talk about something serious for a moment. Rigging is one of the most dangerous jobs in construction and industrial settings. When things go wrong, people die.

The Stakes Are High

According to data from construction safety organizations, rigging-related accidents account for a significant percentage of construction fatalities each year. Failed rigging can result in:

- Dropped loads crushing workers below

- Rigging equipment striking personnel

- Crane tip-overs caused by overloading

- Structural collapses when loads impact buildings

- Workers falling while setting up rigging at height

These aren’t just statistics. Every one represents someone’s parent, child, or friend who didn’t come home from work.

Common Causes of Rigging Accidents

Equipment Failure: Using damaged or improperly rated equipment is a leading cause of accidents. That’s why inspection is so critical.

Improper Load Securing: If a load isn’t attached correctly, it can slip free during the lift. This might happen due to using the wrong hitch configuration or not accounting for the load’s center of gravity.

Exceeding Capacity Limits: Whether it’s overloading a sling, a crane, or any other component, exceeding rated capacities is asking for disaster.

Poor Communication: Misunderstandings between riggers and crane operators or confusion about signals can lead to unexpected movements and accidents.

Environmental Factors: Wind, rain, ice, extreme temperatures—all affect rigging safety. Sometimes the right call is to postpone operations until conditions improve.

Lack of Training: Inexperienced or improperly trained riggers simply don’t know what they don’t know, and that knowledge gap can be fatal.

Safety Best Practices

Never Take Shortcuts: When you’re under time pressure, it’s tempting to skip steps. Don’t. The procedure exists for a reason.

Inspect Everything, Every Time: Even if you used the same equipment yesterday, inspect it again today. Conditions change, equipment degrades.

Communicate Clearly: Confirm everyone understands the plan before starting. Don’t assume.

Know Your Limits: Both equipment limits and your own capabilities. If you’re not qualified or comfortable with a particular lift, speak up.

Use Proper PPE: Hard hats, safety glasses, gloves, high-visibility clothing, and fall protection when working at heights aren’t optional.

Plan for Emergencies: Know what to do if something goes wrong. Where’s the nearest first aid? How do you signal an emergency stop? Who calls 911?

Rigger Salary and Career Outlook

Let’s talk about the practical side: what can you expect to earn as a rigger, and is there job security?

Salary Expectations

According to recent industry data, rigger salaries vary significantly based on several factors:

Entry-Level Riggers: Typically earn between $35,000-$45,000 annually as they’re learning the trade.

Experienced Riggers: With several years under their belt, riggers commonly make $50,000-$70,000 per year.

Lead or Master Riggers: Those with advanced certifications and extensive experience can earn $70,000-$90,000 or more.

Specialized Riggers: Offshore oil and gas riggers or those working in hazardous environments often command premium wages, sometimes exceeding $100,000 annually when factoring in overtime and hazard pay.

Location matters too. Riggers in major metropolitan areas or regions with booming construction typically earn more than those in rural areas, though cost of living is higher in those locations.

Many riggers are union members, which can provide additional benefits like health insurance, pension plans, and standardized pay scales.

Job Outlook

The career outlook for riggers remains strong for several reasons:

Ongoing Construction: Infrastructure needs constant maintenance and expansion. Bridges, buildings, power plants, and transportation systems all require riggers.

Aging Workforce: Many experienced riggers are approaching retirement, creating opportunities for new workers entering the trade.

Renewable Energy Growth: Wind turbine installation and maintenance requires specialized rigging skills, creating a growing niche market.

Entertainment Industry Recovery: As live events rebound, demand for entertainment riggers continues to increase.

Specialized Skills: Good riggers are hard to find. Unlike some trades where automation threatens jobs, rigging requires human judgment, problem-solving, and adaptability that robots can’t replicate.

Industries That Employ Riggers

Riggers find work across a surprisingly diverse range of industries. Here are the major sectors:

Construction

This is the largest employer of riggers. Every major construction project needs rigging expertise—whether it’s commercial buildings, residential complexes, hospitals, schools, or infrastructure.

Oil and Gas

Both onshore and offshore operations require riggers to handle drilling equipment, pipe sections, and heavy machinery in challenging environments.

Manufacturing

Factories employ riggers to install and maintain production equipment, reconfigure assembly lines, and handle materials.

Maritime and Shipping

Ports, shipyards, and cargo operations need riggers for loading/unloading ships, building vessels, and handling marine equipment.

Entertainment and Events

Concerts, festivals, theater productions, sporting events, and exhibitions all require rigging for lighting, sound, staging, and special effects.

Utilities and Power Generation

Power plants (whether coal, gas, nuclear, or renewable) need riggers for equipment installation and maintenance. Wind farms are a growing source of rigging work.

Mining and Quarrying

Mining operations use riggers to move heavy machinery and materials in demanding conditions.

Telecommunications

Cell tower construction and maintenance requires riggers who are comfortable working at extreme heights.

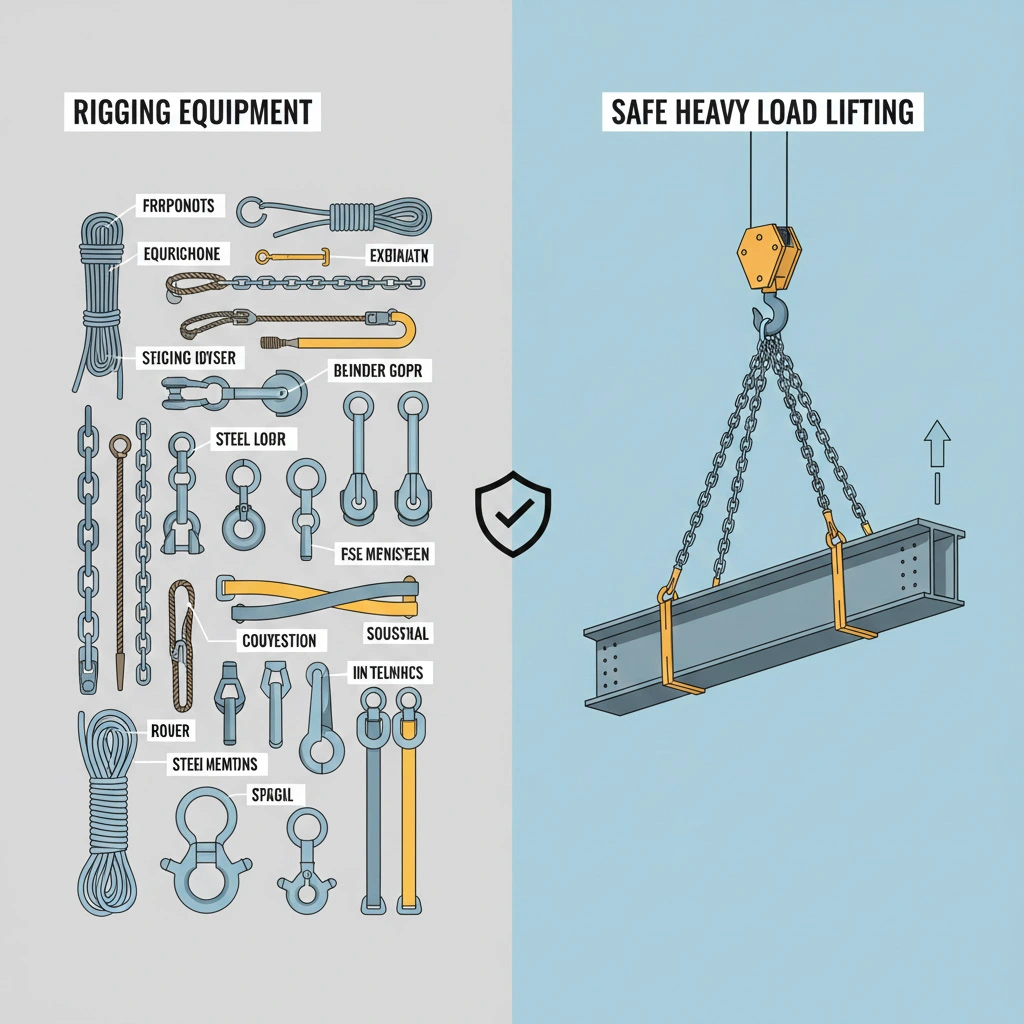

Rigging Equipment: Tools of the Trade

Let’s get familiar with the equipment riggers use every day. Understanding these tools is fundamental to the profession.

Wire Rope Slings

What They Are: Cables made from braided steel wire, available in various diameters and configurations.

When to Use Them: Heavy loads, abrasive materials, high-temperature applications. Wire rope is incredibly strong and durable.

Limitations: Can be damaged by sharp edges, kinking, or crushing. Must be inspected carefully for broken wires or other degradation.

Synthetic Slings

What They Are: Made from synthetic fibers like nylon or polyester in flat webbing or round configurations.

When to Use Them: When you need to avoid scratching or denting the load (like painted equipment or polished machinery), or when working around electrical hazards.

Limitations: Less abrasion-resistant than wire rope, can be damaged by chemicals or UV exposure, have lower temperature ratings.

Chain Slings

What They Are: Lengths of alloy steel chain with hooks or other fittings.

When to Use Them: Extremely durable, resistant to abrasion and heat, excellent for rough or jagged loads.

Limitations: Heavy to handle, can damage delicate loads, susceptible to impact damage.

Shackles

What They Are: U-shaped connectors with a pin or bolt to close the opening, used to connect rigging components.

Types: Anchor shackles (wider body for multi-directional loading) and chain shackles (narrower for inline loading).

Critical Points: Must be properly sized for the load, pins must be fully tightened, never use a shackle that’s been deformed or cracked.

Hooks

What They Are: Forged steel hooks that connect to crane blocks or the ends of slings.

Safety Features: Most hooks have safety latches to prevent slings from slipping off during lifts.

Inspection: Hook opening (throat) must not exceed manufacturer specifications—stretched hooks must be taken out of service.

Pulleys and Blocks

What They Are: Wheeled devices that change the direction of force or provide mechanical advantage.

Applications: Used to create multi-part lines that can lift heavier loads than the equipment could handle with a single line.

Maintenance: Sheaves (wheels) must turn freely, bearings need lubrication, frames must be structurally sound.

Hoists and Come-Alongs

What They Are: Mechanical devices for lifting or pulling loads.

Types: Manual chain hoists, lever hoists (come-alongs), electric chain hoists, and wire rope hoists.

Usage: Ideal for moving loads in tight spaces or when a crane isn’t practical.

Rigging Hardware

Various specialized components include:

- Eyebolts: Threaded bolts with a loop, screwed into loads to provide lifting points

- Beam clamps: Attach to steel beams without drilling or welding

- Turnbuckles: Adjustable tensioners for leveling loads

- Spreader bars and lifting beams: Distribute load forces and maintain specific geometries

Common Rigging Configurations and Hitches

How you attach rigging to a load dramatically affects capacity and safety. Here are the fundamental configurations:

Vertical Hitch

Configuration: Single sling running straight up from the load to the lifting point.

Capacity: Uses 100% of the sling’s rated capacity (for straight vertical lifts).

When to Use: Simple lifts where the load has a central attachment point and is balanced.

Limitations: Load must be balanced, otherwise it will tilt. Not suitable for loads without dedicated lifting points.

Choker Hitch

Configuration: Sling wraps around the load with one end passing through a loop or eye in the other end, forming a noose that tightens when lifted.

Capacity: Typically reduces sling capacity to about 75% of rated capacity due to the sharp bend.

When to Use: Excellent for securing loads that might slip, like pipes or round objects.

Caution: Choker can damage soft or polished surfaces as it tightens.

Basket Hitch

Configuration: Sling passes under the load with both ends attached to the hook, forming a U-shape.

Capacity: Can handle up to 200% of the sling’s rated capacity (double the vertical hitch) because the load is shared between two legs.

When to Use: Maximizes capacity, good for balanced loads with secure bottoms.

Consideration: Sling angle matters—steeper angles reduce capacity.

Bridle Hitch

Configuration: Multiple slings attached to different points on the load, all connecting to a single lifting point.

Purpose: Distributes weight across multiple attachment points, useful for large or irregularly shaped loads.

Critical Factor: All legs must share the load evenly. Uneven loading can overstress some slings while others carry little weight.

Rigger Safety Regulations and Standards

Rigging doesn’t operate in a regulatory vacuum. Multiple organizations set standards that riggers must follow.

OSHA (Occupational Safety and Health Administration)

In the United States, OSHA sets and enforces workplace safety regulations, including specific standards for rigging operations:

29 CFR 1926 Subpart CC: Covers crane and derrick operations in construction, including rigger qualification requirements.

Qualification Requirements: OSHA mandates that riggers must be either certified or qualified through training and evaluation by their employer.

Inspection Requirements: Rigging equipment must be inspected before each use and periodically by a competent person.

Capacity Limits: Equipment must not be loaded beyond its rated capacity, and derating factors (like sling angles) must be applied.

ASME (American Society of Mechanical Engineers)

ASME B30 Standards: Cover various types of hoisting and rigging equipment, providing technical specifications and safety requirements.

B30.9: Specifically addresses slings and is considered the industry bible for sling use and inspection.

B30.26: Covers rigging hardware like shackles, hooks, and other lifting accessories.

ANSI (American National Standards Institute)

Works with industry groups to develop consensus standards for rigging practices, equipment design, and safety procedures.

Industry-Specific Regulations

Some sectors have additional requirements:

MSHA (Mine Safety and Health Administration): Regulates rigging in mining operations.

Maritime Regulations: Coast Guard and international maritime standards govern ship and port rigging.

Entertainment Industry: ESTA (Entertainment Services and Technology Association) and PLASA provide standards for entertainment rigging.

Rigging Accidents: Learning from Mistakes

While it’s sobering to discuss, examining rigging accidents helps prevent future tragedies. Here are some real-world scenarios (anonymized) that illustrate critical lessons:

Case Study 1: The Invisible Damage

What Happened: A wire rope sling looked fine externally but had internal broken wires from previous overloading. During a routine lift, it failed catastrophically, dropping a 3-ton load.

The Lesson: External inspections aren’t always enough. Riggers must look for subtle signs of internal damage—kinks, areas of reduced diameter, unusual flexibility—and when in doubt, remove equipment from service.

Case Study 2: The Capacity Miscalculation

What Happened: A rigger selected a sling rated for 5 tons for a 4-ton load. Sounds safe, right? But the sling was used in a choker configuration at a sharp angle, reducing its capacity to less than 3 tons. The sling failed.

The Lesson: Rated capacity is just the starting point. You must account for hitch configuration, sling angles, and environmental factors. When calculations show you’re close to limits, select higher-capacity equipment.

Case Study 3: The Communication Breakdown

What Happened: A rigger signaled the crane operator to “boom up” (raise the boom). The operator, expecting a different signal sequence, interpreted it as “hoist up” (raise the load). The unexpected movement caused the partially secured load to shift and strike a worker.

The Lesson: Never assume. Establish clear communication protocols before starting operations, confirm everyone understands the signals, and when there’s any doubt, stop and clarify.

Case Study 4: The Environmental Factor

What Happened: Wind gusts caused a tall, flat load to act like a sail. The load swung violently, pulling the crane off balance.

The Lesson: Weather isn’t just a comfort issue—it’s a safety factor. High winds, ice, lightning, extreme heat or cold can all affect rigging safety. Know the weather limits for your operations and don’t be pressured to work in unsafe conditions.

The Future of Rigging: Technology and Innovation

Rigging might be an ancient profession, but it’s not stuck in the past. Here are some ways technology is changing the trade:

Load Monitoring Systems

Modern rigging increasingly incorporates electronic load cells that provide real-time weight information. Riggers can see exactly how much load is on each sling or crane line, allowing for better load distribution and preventing accidental overloading.

Wireless Communication

Traditional hand signals work, but wireless headset systems allow for more detailed communication between riggers, crane operators, and other personnel—particularly valuable in noisy environments or when visual contact is limited.

Synthetic Rope Advances

New high-strength synthetic fibers rival steel in strength while being lighter, more flexible, and resistant to corrosion. Some synthetic ropes can even float, making them valuable in marine applications.

Remote Monitoring and IoT

Some rigging equipment now includes sensors that track usage cycles, alert operators to overload conditions, and even predict when components are approaching end-of-life based on stress history.

Virtual Reality Training

VR systems allow trainee riggers to practice complex lifts in simulated environments where mistakes don’t have real-world consequences. This technology supplements (but doesn’t replace) hands-on training.

Drones for Inspection

Unmanned aerial vehicles can inspect rigging setups at extreme heights or in hazardous locations, providing visual documentation without exposing workers to unnecessary risks.

Frequently Asked Questions About Riggers

Q: Do I need to be extremely strong to be a rigger?

While physical fitness helps, being a rigger is more about knowledge, technique, and problem-solving than raw strength. You use mechanical advantage, proper technique, and teamwork to move heavy loads—not muscle alone. That said, the work is physically demanding, so being in reasonable shape is important.

Q: How long does it take to become a certified rigger?

It varies. Formal apprenticeship programs typically last 3-4 years. However, you can obtain basic rigging certifications in a matter of weeks through intensive training courses, though these provide entry-level credentials, not the deep expertise that comes with years of experience.

Q: Is rigging dangerous?

Yes, it can be. When proper procedures are followed, equipment is maintained, and safety protocols are respected, rigging is manageable. But there’s no room for carelessness—mistakes can be fatal.

Q: Can women be riggers?

Absolutely. While rigging has historically been male-dominated, women are increasingly entering the trade. The physical demands can be managed with proper technique and equipment, and the mental skills required—attention to detail, communication, problem-solving—have nothing to do with gender.

Q: What’s the difference between a rigger and a crane operator?

Riggers prepare loads for lifting and guide operations from the ground. Crane operators control the crane itself. They work closely together, but they’re distinct roles requiring different skills and certifications.

Q: Do riggers work year-round?

In construction, work can be seasonal depending on your location and climate. In industries like manufacturing, oil and gas, or entertainment, work may be more consistent. Some riggers travel to where the work is, following construction projects or touring with entertainment productions.

Q: What’s the most challenging aspect of being a rigger?

Many riggers say it’s the responsibility. Lives depend on you doing your job correctly. Every lift requires focus and attention—you can’t have an “off day” when tons of material are hanging over people’s heads.

Final Thoughts: Is Rigging Right for You?

Rigging isn’t for everyone, and that’s perfectly fine. It’s physically demanding, mentally challenging, and comes with significant responsibility. But for the right person, it’s an incredibly rewarding career.

If you’re someone who:

- Enjoys problem-solving and figuring out how things work

- Takes pride in precision and getting details right

- Doesn’t mind physical work and outdoor conditions

- Values being part of a team where everyone looks out for each other

- Wants to see tangible results from your efforts (that building went up because of what you did)

- Appreciates good pay for skilled work

…then rigging might be worth exploring.

The trade offers solid earning potential, job security, opportunities to specialize, and the satisfaction of knowing your expertise keeps people safe. Every skyscraper, every bridge, every concert stage exists because skilled riggers did their job right.

Not a bad legacy for a day’s work.

Ready to learn more about rigging or start your career in this essential trade? Contact local trade schools, apprenticeship programs, or construction companies in your area to explore opportunities. The industry needs skilled riggers, and the time to start is now.